TEST THE SOIL (EARTHWORKS)

Prior to performing any water-harvesting earthworks, you should test your soil’s physical characteristics at the proposed sites of your ponds or dams, swales, drains…

The purpose of these tests is to measure the quality of your soil from a water-management perspective so you know what to expect, the suitability of the sites in question and how to size and design the water-management features.

You can do all of the tests with no special training and no special tools; the only real requirement is time and willingness to dig test holes.

The entire soil testing protocol consists of conducting four simple tests at the desired spot, looking at the 1. soil’s compaction, 2. profile, 3. texture and 4. drainage.

Note: when selecting a place to conduct your test, choose a spot that is representative of the site, i.e. the soil you’d find there would be the soil you’d find across the whole proposed site. In case of differences in soil type across the proposed site, choose multiple representative spots.

What you’ll need?

Estimated cost: 0$ – $30

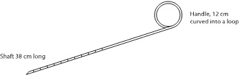

- A 50 cm (20 in) length of 3.15 mm (10 gauge) high-tensile wire.

- A bucket of water

- A shovel

- A timer

Estimated time: 10 min.

Once you’ve decided where you want to test your soil, you can do the first test and see how compacted your soil is. This test will reveal how hard it’s going to be to dig the soil and what kind of runoff/infiltration into the soil you can expect.

To test the compaction of the soil you’ll need a DIY penetrometer. You could buy sophisticated penetrometers, albeit for hundreds of dollars, but you can also make your own inexpensive version.

Estimated time: 20 min.

Once you’ve tested the compactness of the soil, it’s time to dig a test hole at the same spot. You’ll use this soil pit for the remaining three soil tests.

First, you’ll want to check your soil profile – identify layers or horizons of the soil. Performing this test will reveal the depth of your topsoil, subsoil and, depending on how deep you can dig, the depth of the underlying weathered rock or bedrock.

This is important information from a water-management perspective as the depth and thickness of these layers will determine what you’ll be to do.

The soil layers compromising the soil profile will be approximately parallel to the ground surface. You’ll be able to distinguish each layer from the one above or below as they’ll be different

Note: If you’re testing your soil for a pond site, depending on its desired depth, you’ll probably need to dig a much deeper test hole than the one outlined here.

Estimated time: 10 min.

Now when the soil profile is exposed you’ll want to evaluate soil texture; the proportion of sand, silt, and clay in your soil. The texture influences the rate at which water enters and moves through soil, which is of primary concern as we are building water harvesting earth structures.

Understanding soil texture will help you in deciding whether you can build a compacted pond without a liner, how wide and deep should the swales be and how well the harvesting drains will work.

The three building blocks of soil sand, silt, and clay give different properties to

Estimated time: 10 min. – 24h

Finally, while you have that soil pit dug out, you can do a simple test to check the soil drainage there. This will show you how porous the soil is and what its water-holding capacity will be, so you’ll know how your ponds, swales, and harvesting drains will behave once they are full of water.

The results of this test might vary depending if the soil is completely dry or fully saturated but you’ll want to get a general idea of soil drainage from the water-management perspective right there and then. Just bear that in mind if the current soil conditions are on one side of the extreme.

Note: if you’re specifically testing the soil to see how suitable it is for building a pond you’ll probably have to fill the hole with water twice. First to totally saturate the soil and then to do the measurements. This will give you a more accurate test reading.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

Copyright © 2023 Permaculture Apprentice. All Rights Reserved | Privacy | Terms of Service |Member Agreement

0 Comments